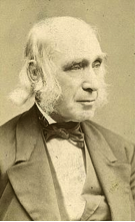

Amos Bronson Alcott was a 19th century American writer, philosopher and experimental teacher. In his educational role he turned the traditional teaching method on its head, preferring to engage his students in conversation rather than being the autocratic figure at the front lecturing to a silent class. He had a great social conscience outside of the classroom as well, being a champion for women’s rights and a supporter of the abolition of slavery.

Amos Bronson Alcott was a 19th century American writer, philosopher and experimental teacher. In his educational role he turned the traditional teaching method on its head, preferring to engage his students in conversation rather than being the autocratic figure at the front lecturing to a silent class. He had a great social conscience outside of the classroom as well, being a champion for women’s rights and a supporter of the abolition of slavery.

He was born on the 29th November 1799 in Wolcott, Connecticut. He had very little formal education, preferring to wander the countryside around his childhood home of Spindle Hill. He later said of this time:

He had some private tutoring but by the age of 15 he was apprenticed to a clock maker in nearby Plymouth. He also tried his hand as a travelling salesman but, before long, he turned to teaching. Even in this profession though he did not stay in one place for long. Perhaps his longest engagement was at the Temple School in Boston and he wrote two books about his experiences there. At this time he was heavily involved in transcendentalism and was a good friend to the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson. Alcott had plans to create a kind of commune of “human perfection” and he named his futuristic project “Fruitlands”. Perhaps 19th century America was not quite ready for this kind of concept and it failed after only seven months.

It seemed that he was always struggling financially, a state of affairs that lasted most of his lifetime. He married in 1830 and Louisa May, one of his four daughters, grew up to be the author of the novel Little Women. The book was based on her life growing up in Connecticut and her best-selling novelist status enabled the whole family to be better off. Four years later Alcott opened his Temple School and attracted some 30 students, mostly from well off families. Unfortunately it received savage reviews in the Boston press and the school’s fortunes rapidly deteriorated.

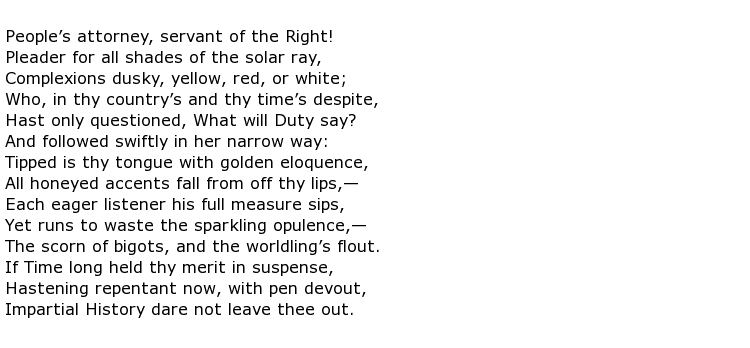

He taught in various establishments later in his life and also collaborated with his daughter Louisa May on the writing of a memoir of his wife, Abby May, who died in 1877. It was never finished though as Alcott was so wracked with grief and, according to Louisa, “had become restless with his anchor gone.” The memoir was abandoned and Louisa burned the majority of her mother’s papers. His own published titles included Tablets, in 1868, and an account of his family’s life at a house called “Concord” which he called Concord Days (1872). His poems were often about real-life characters of the day such as Thoreau, Garrison and his great friend, the poet Emerson. Here is one about a famous American lawyer, called Wendell Phillips:

Alcott, perhaps harking back to his beliefs in transcendentalism, wrote a lyrical line about Emerson having visited his friend who was sick and confined to his bed. He wrote:

Emerson died the very next day. Incredibly, something similar happened when he was on his own deathbed. During a visit from Louisa May, Alcott knew he was dying and said to her:

“I am going up. Come with me.”

Her response was “I wish I could” and Amos Bronson Alcott died three days later on the 4th March 1888. He was 88 years old. Louisa May did, indeed, follow her father “up”, as she died two days later.