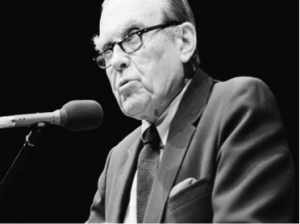

Considered one of the greatest Polish literary figures Czeslaw Milosz was born the 30th June 1911 to a Catholic family in the small village of Szetejnie, which was part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. His father Aleksander was a qualified civil engineer, whilst his mother Weronika was of noble descent. Fluent in Polish, Lithuanian, Russian and French, he saw himself as neither Polish nor Lithuanian saying:

Considered one of the greatest Polish literary figures Czeslaw Milosz was born the 30th June 1911 to a Catholic family in the small village of Szetejnie, which was part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. His father Aleksander was a qualified civil engineer, whilst his mother Weronika was of noble descent. Fluent in Polish, Lithuanian, Russian and French, he saw himself as neither Polish nor Lithuanian saying:

His family had moved to Lithuania to avoid political disruption in Poland and Milosz later defected to the West to escape the Communist regime which came to power after World War Two.

Following a Catholic school education he went on to study law at University. The university he attended was Stefan Batory. In 1931 the fancy took him to visit Paris , forming a poets group, Zagary, and bginning to have his poems published in the university magazine. His master’s degree in law was awarded him in 1934 and in the same year his first full volume of poetry, Poemat o czasie zastyglym (Poem of the Frozen Time) appeared. Milosz composed all of his poetry and essays in Polish. He also translated into Polish the Old Testament psalms. He worked as a commentator for Radio Wilno but was dismissed, largely because of his left-wing beliefs. When Poland was invaded in 1939 Milosz worked with the underground resistance movement in Warsaw. He was not involved in the Warsaw Uprising because he considered it to be a “doomed military effort” and saw the leadership as right-wing and dictatorial. Throughout the Nazi occupation of Poland Milosz was active in helping Polish Jews. For this he was awarded the medal of the Righteous Among The Nations by Israel in 1989. After the war he became cultural attaché to the Communist People’s Republic of Poland, first in the USA then in Paris. He received criticism from his own countrymen when, in 1951 he absconded and was able to obtain political asylum in France where he spent the next decade as a writer. His 1953 novel, The Captive Mind, was written to show how intellectuals behave under a repressive regime and became essential reading for political science students.

In 1960 Milosz emigrated to America to take up a post as Slavic Languages professor at the UCLA and obtained US citizenship in 1970. In 1978 he was awarded the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature. His contentment with living in California is reflected in his poem The Magic Mountain, from 1985:

In 1980 Milosz receivedva Nobel Prize for his Literature, finally bringing him to the attention of the Polish people. (His work had been prohibited by Polands Communist government for many years.) Following the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 he was finally able to visit Poland again and bought an apartment in Krakow, dividing time between here and California. His new-found acceptance in Poland was demonstrated when workers in Gdansk showed a memorial to comrades who had been shot by the police and on which was an inscription taken from one of Milosz’s poems. People began to see his work as the work of a thinker who related the history of his people in poems concerning loss, despair and the diminishing of religious beliefs.

Milosz continued to write into his nineties and in 2001 published a translation of a 1957 work, A Treatise on Poetry, which reflected on Poland between the two world wars and the history of Polish poets throughout. He died on August 14th 2004 having outlived two wives. He is buried in Krakow’s Skalka Roman Catholic church.