Born in 1772 towards the back end of the Le Dynasty in Vietnam, Ho Xuan Huong is considered one of the country’s greatest poets. Brought up at a time of turmoil and conflict, little is known about her life but her work earned her the title of The Queen of Nom Poetry. Considered one of the cultural icons of Vietnam, she was popular for her irreverent style and highly erotic verse that was often shocking for the times.

Born in 1772 towards the back end of the Le Dynasty in Vietnam, Ho Xuan Huong is considered one of the country’s greatest poets. Brought up at a time of turmoil and conflict, little is known about her life but her work earned her the title of The Queen of Nom Poetry. Considered one of the cultural icons of Vietnam, she was popular for her irreverent style and highly erotic verse that was often shocking for the times.

What we know of Ho Xuan Huong’s life occurs against a background of national turmoil and social discord. She spent her childhood in Hanoi and began writing poetry at an early age. She was popular for her humorous style and subtle verse from which we can discern that she may have been married on two occasions (her poems mention two separate husbands). Her second marriage saw her acting as a highly ranked concubine, a position she was not completely at ease with, once commenting that it was like being an unpaid maid.

Thankfully for Ho Xuan, her second husband died barely six months after they were married and she spent the rest of her days living alone beside the lake in Hanoi in a small house. Her poems reveal that she was permitted to travel at the time and that she earned a living as a teacher. She was however a fairly independent woman, unusual for the times, and committed to fighting against what passed for normal society.

Her poems are laced with sexual double meaning and she wrote most of her works in Nom, something which raised the status of Vietnamese as a language for literature. She was also able to write in classic Chinese and some of her poems have recently been discovered that reveal this.

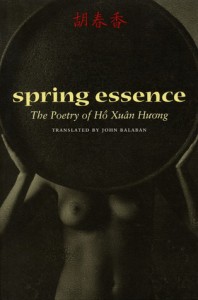

Over the years Nom fell into disuse and became an archaic script that only a few people in Vietnam could read in the 20th Century. There was, however, a strong oral tradition that kept her work alive for the people. It led to her work not being translated for Western audiences for a long period of time until a small American Press, Copper Canyon, published Spring Essence in 2001.

Ho Xuan Huong was remarkable for her time in that she lived in an age when Confucian philosophy forbade the depiction of nudity in art and writing poetry with erotic undertones was almost unheard of, particularly for a woman. Not only that but she wrote several poems that poked fun at Buddhist traditions and the feudal state. Had the Vietnamese not held poetry in such high esteem, it is possible that Ho Xuan Huong might well have been severely punished for her art.

As with her life, not much is known of Ho Xuan Huong’s death though it is generally accepted that she passed away in 1822 when she was 60.