Jack Spicer had a curious name for the short poems that he wrote in the early part of his writing career. He called them “one night stands” and this was actually part of the title of one of his published collections (One Night Stands and Other Poems, pub 1980). He was at his peak in the 1950s when he and a few other poets got together to form their version of the “Beat Movement” on the west coast of the United States. All of those participating were gay. He and his compatriots were great followers of earlier poets like Arthur Rimbaud and Federico García Lorca.

Jack Spicer had a curious name for the short poems that he wrote in the early part of his writing career. He called them “one night stands” and this was actually part of the title of one of his published collections (One Night Stands and Other Poems, pub 1980). He was at his peak in the 1950s when he and a few other poets got together to form their version of the “Beat Movement” on the west coast of the United States. All of those participating were gay. He and his compatriots were great followers of earlier poets like Arthur Rimbaud and Federico García Lorca.

Spicer was born in January 1925 in Los Angeles and progressed through high school before going on to the University of Redlands when he was 18 years old. He stayed in academic surroundings during the ten years following the end of WWII, working as a research linguist at Berkeley. He dabbled with writing his own poetry and tried to get some of it published, although he always said that he did not write to publish. He teamed up with fellow poets Robert Duncan and Robin Blaser to form what they called “The Berkeley Renaissance”.

They were quite open about their homosexuality which was probably unusual for that time in history and were happy to mentor younger students interested in poetry and the group’s so-called “queer genealogy”. They were, of course, referring to the likes of Rimbaud and Lorca. Poetry produced by Spicer during this period was to remain unpublished until 15 years after his death and came out in the aforementioned One Night Stands collection.

In 1954 he was a driving force behind the “Six Gallery” in San Francisco, and it was here where the Beat Generation was launched. He decided to try his luck in New York a year later, followed by Boston where he met up with his old friend Robin Blaser. Once again the pair sought out the company of like-minded artists and poets such as Joe Dunn and John Wieners.

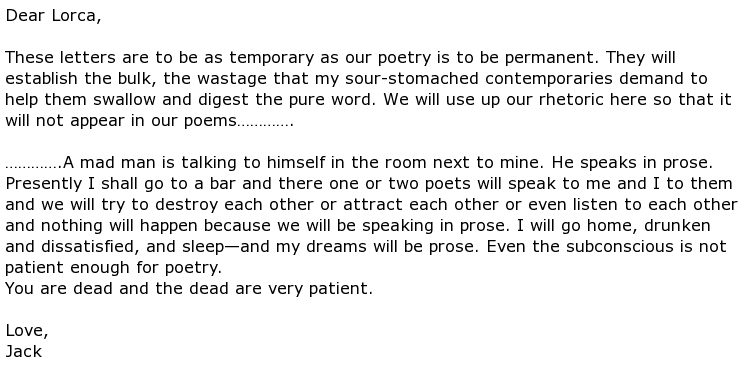

Spicer was becoming dissatisfied with his own writing though, believing that the short poems that he had so far written were unworthy of further time and attention. He favoured the concept of the “serial poem” and began his work on the great work After Lorca. He changed his style completely for this and followed a practice that he called “poetry as dictation”. An example is shown below. It is the first and last sections of his “poem” After Lorca and is clearly written in a prose style, deliberately at odds with traditional poetic expectations, but is effective, nonetheless:

He wanted to share his new style of writing and, in 1957, created a poetry workshop at San Francisco State College. He called it “Poetry as Magic”. There was also a meeting called “Blabbermouth Night” held at a bar in the city for literature aficionados. Spicer sometimes hosted the competitions held at this meeting, encouraging others to share his view of poetry as being dictated to the poet. He was almost certainly using his previous experience as a research linguist to portray this new way of writing and he had some very forthright views on the use of language, especially in poetry. His final book, simply called Language, has strong references to such linguistic concepts as morphemes and graphemes. Poets who followed in Spicer’s literary footsteps were certainly inspired by his ground-breaking work.

Spicer died tragically young but he left a great legacy of work behind him including the famous detective novel The Tower of Babel (pub 1994) and a collection of the best of his work called My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer (pub 1998).

Jack Spicer died on 17 August 1965 of acute alcoholism, aged 40.