Jessie Redmon Fauset was an African American writer, literary editor and teacher. During the 1920s she was one of the first to present a true record of African American history through her poetry and essays, introducing characters who were of the professional class. Writers before her, and sometimes since, had focused on the downtrodden, the disadvantaged, the enslaved. Along with others of the Harlem Renaissance she was determined to set the record straight, offering what had previously been inconceivable ideas to predominantly white American society. It was an uphill battle but she tried to present racial discrimination as a “passing phase” and to promote feminism.

Jessie Redmon Fauset was an African American writer, literary editor and teacher. During the 1920s she was one of the first to present a true record of African American history through her poetry and essays, introducing characters who were of the professional class. Writers before her, and sometimes since, had focused on the downtrodden, the disadvantaged, the enslaved. Along with others of the Harlem Renaissance she was determined to set the record straight, offering what had previously been inconceivable ideas to predominantly white American society. It was an uphill battle but she tried to present racial discrimination as a “passing phase” and to promote feminism.

She was born Jessie Redmona Fauset on the 27th April 1882 in a small town in New Jersey that is now called Lawnside. Her father was an African Methodist Episcopal minister and she was the seventh child borne by her mother who tragically died when Jessie was very young. The family would grow ever larger when her father remarried a white Jewish woman who brought three children to the marriage and who then went on to produce three more. Despite the enormity of the task all of the children received a good education. Jessie first attended the Philadelphia High School for Girls and then went on to read classical languages at Cornell University in upstate New York. She graduated in 1905, taking with her a degree and Phi Beta Kappa honours which was an unusual achievement for a black woman at that time.

Fauset entered teaching at M Street High School, an establishment exclusively for black students in Washington DC. Her subjects were Latin and French and she spent her summers studying at La Sorbonne in Paris. After fourteen years she left to become the literary editor of The Crisis, a magazine aimed at and run by members of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). Her seven years in this post boosted her reputation as a talented writer and public speaker and she remained an active contributor to the Harlem Renaissance of black writers and artists, encouraging others to write freely and honestly about black racial issues. Future writers such as Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes benefitted from being mentored by Jessie Fauset.

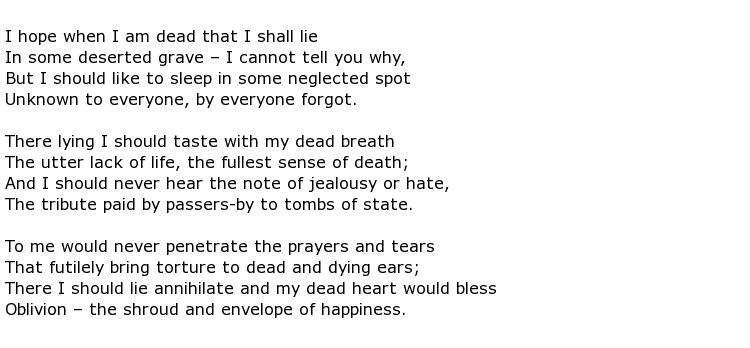

During the 1920s she published four novels, all focusing on professional, middle class black people and she also went back to teaching during this period, continuing her work until 1944. Her time at The Crisis meant that she had the opportunity to publish her own poetry and short stories as well as those of others and they were well received by both readers and literary critics alike. She often wrote of grim, sometimes distasteful subjects such as in her poem Oblivion which is her apparent wish to lie undisturbed, unvisited in a lonely grave far from everyone. Whether or not she really wanted to be forgotten in this way is an unknown, but it is a powerful short poem nevertheless. It is reproduced here:

The early to mid-20th century years were hard times for many people with wars and economic depression dominating all around and it is not surprising that literature was of secondary concern. Probably for this reason her work was largely forgotten for a while, only coming back to prominence when the feminist movement gathered pace in the 1970s. Once more Fauset was recognised as a significant contributor to African American literature.

Jessie Redmon Fauset died of heart failure on the 30th April 1961, aged 79.