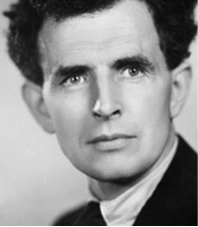

Patrick MacGill came from County Donegal, a part of Ireland that has, through history, produced a number of poets and artists. Perhaps it is the romantic nature of the landscape that inspires people to write about it or draw what they see. MacGill rose from humble beginnings to become a revered Irish poet. He is commonly known as “The Navvy Poet” due to the line of work that he followed before taking up the pen. He was one of the thousands of Irish labourers who worked all over Britain digging out the trenches that became the network of canals, laying the roads or blasting through hillsides to make way for the railways. They were called “navvys” which was a shortened version of navigational engineer.

Patrick MacGill came from County Donegal, a part of Ireland that has, through history, produced a number of poets and artists. Perhaps it is the romantic nature of the landscape that inspires people to write about it or draw what they see. MacGill rose from humble beginnings to become a revered Irish poet. He is commonly known as “The Navvy Poet” due to the line of work that he followed before taking up the pen. He was one of the thousands of Irish labourers who worked all over Britain digging out the trenches that became the network of canals, laying the roads or blasting through hillsides to make way for the railways. They were called “navvys” which was a shortened version of navigational engineer.

Patrick MacGill was born on Christmas Eve, 1899 in the small town of Glenties in Donegal. He suffered a poor upbringing where families seemed to be permanently enslaved by local money lenders and by the strict regime of their parish priests. Young men were sold as virtual slaves at the village hiring fairs. Patrick suffered this fate at the age of 14, a necessity at the time as his family could not afford to feed him. He laboured on the farms of Ireland and Scotland and his time in Scotland led to him becoming a navvy.

He saw this as a relatively well paid job but, of course, that pay was often earned with great risk to life and limb. Safety standards were something for the far distant future and speed of construction was the mantra that they all had to live by. While most navvys spent their earnings on drink and gambling MacGill was of a much more sensitive nature and he invested his money in books, and his time in the learning that he never had when he was a boy. He taught himself to read and write French and German and he was inspired by works such as Les Miserables. He saw the struggles of the poor people of France virtually mirroring his own existence and his future work would feature themes exploring social conscience. His first collection of poems came out in 1911 and was all about his life as a navvy – Gleanings from a Navvy’s Scrapbook.

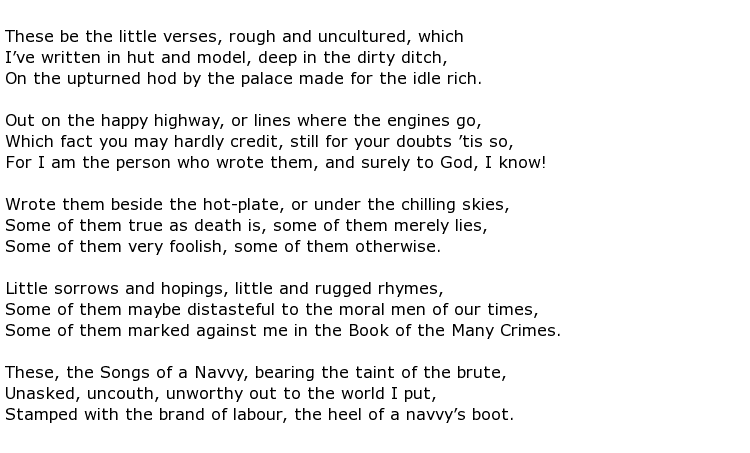

Here is an example of one of his poems about this life, called By The Way:

He had no literary agents on his side so ended up selling the book himself, literally hawking it around. He was fortunate that he sold a copy to a journalist called Neil Munro who had good contacts in British literary circles at that time. Munro was credited with making people aware of the work of Kipling and Conrad so MacGill struck lucky with that particular sale.

The “navvy poet” soon became famous around the world and he was engaged as a writer in London’s Fleet Street for the Daily Express newspaper. Even better was in store for him though when he was recruited by Canon Dalton, a former personal tutor to royalty, to translate some ancient manuscripts. At this time MacGill wrote a novel that firmly established his name. Children of the Dead End was virtually autobiographical and it sold well almost everywhere except in his native Ireland. The criticism of the Catholic clergy there did not go down well.

A blossoming writing career was curtailed by the outbreak of WWI and MacGill served in military intelligence and as a stretcher bearer. He was gassed accidentally and invalided back home. He soon took up writing again, producing a collection of poems called Songs of Donegal. Further novels and a war-based play called Suspense followed and then, in 1930, he emigrated to the United States. He was to spend the rest of his life there.

Patrick MacGill died in Florida in November 1963, aged 73.