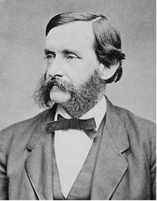

Thomas Wentworth Higginson was a man who lived his life forever conscious of the needs and rights of those less fortunate than himself. An occasional poet and author of hard-hitting articles to American publications he dedicated much of his energy to the abolitionist movement that was gathering pace in the 1840s. He and many other like-minded Americans were appalled that some states still supported the enslavement of black people and he made it his priority that something would be done about it. Never afraid to show the world how he felt about this thorny subject, he took command of the first regiment of black troops during the Civil War. Apart from this he stood up and shouted loudly for the rights of women in society; he believed in equal status and equal rights whatever your gender. In later life he became chief mentor to the poet Emily Dickinson, giving her forthright but constructive criticism from the start.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson was a man who lived his life forever conscious of the needs and rights of those less fortunate than himself. An occasional poet and author of hard-hitting articles to American publications he dedicated much of his energy to the abolitionist movement that was gathering pace in the 1840s. He and many other like-minded Americans were appalled that some states still supported the enslavement of black people and he made it his priority that something would be done about it. Never afraid to show the world how he felt about this thorny subject, he took command of the first regiment of black troops during the Civil War. Apart from this he stood up and shouted loudly for the rights of women in society; he believed in equal status and equal rights whatever your gender. In later life he became chief mentor to the poet Emily Dickinson, giving her forthright but constructive criticism from the start.

He was born Thomas Wentworth Higginson on the 2nd December 1823 in the town of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The family were descended from Puritan immigrants and his father was a merchant and philanthropist. It is likely that Thomas inherited his father’s philanthropical attitudes. He was sent to Harvard college at the age of 13 and the to the arts and literature college Phi Beta Kappa three years later. On graduation he tried his hand at school teaching for two years before going on to theology studies, but the abolitionist cause soon captured Higginson’s attention.

He joined an organisation called the Disunion Abolitionists and wrote a number of anti-war poems. He spoke out against the mal-treatment of workers in New England cotton factories and, in his new role as a minister, he was able to invite the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson and William Wells Brown to his church to give their views. Brown was, at that time, a fugitive slave and there was much lobbying going on about abolishing the practice of hounding former slaves who had managed to escape their shackles. Unfortunately Higginson’s congregation found their new minister a bit too radical for their tastes and he resigned the post.

When the civil war was raging he became Colonel of the First South Carolina Volunteers, a body of men unique in being the first entirely black regiment to give military service. Higginson was also a strong supporter of the even more famous abolitionist John Brown. His support of the movement went well beyond strong words though – he actively participated in attempts to free imprisoned former slaves and suffered injuries in the process.

Before the outbreak of the war though Higginson campaigned tirelessly on behalf of the women’s suffrage movement. He published many papers on the subject including Consistent Democracy: The Elective Franchise for Women. Twenty-five Testimonies of Prominent Men in 1858. Later on he took an active role in the formation of the New England Woman Suffrage Association (1868) and then, a year later, the American Woman Suffrage Association. He wrote prominently in The Woman’s Journal.

Much of Higginson’s work demonstrated his sensitivity to art and humanity and his love of nature. A good example of this is the poem Snowing of the Pines which tells of the bounty that the forest floor receives from the pine trees above, when it is time to shed their summer cloak of pine needles:

Higginson was a constant champion for the repressed and underprivileged and even formed an organisation in support of Russian people who were struggling. This was called the Society of American Friends of Russian Freedom (SAFRF) and he served as vice-president of the organisation in 1907.

In his later years he dedicated a lot of his time to the poet Emily Dickinson and became her constant mentor, critic and friend.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson died on the 9th May 1911, aged 87.