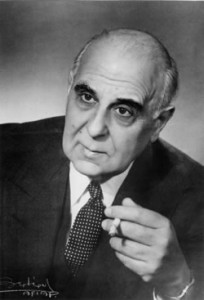

Considered as one of the most influential poets to come out of Greece in the 20th Century, Giorgos Seferis was born in 1900 in Urla, a town near the ancient city of Smyrna. He came from an educated family and his father was a lawyer and poet with his own reputation, allied to the political movement called Venizelism, all of which had an influence on the young Seferis.

Considered as one of the most influential poets to come out of Greece in the 20th Century, Giorgos Seferis was born in 1900 in Urla, a town near the ancient city of Smyrna. He came from an educated family and his father was a lawyer and poet with his own reputation, allied to the political movement called Venizelism, all of which had an influence on the young Seferis.

When he was 14, the family relocated to Athens, the capital of Greece, and he completed his high school education before heading to Paris where he studied for a law degree at the Sorbonne in 1918, graduating 6 years later. At the same time, Greece was in turmoil and his family were forced to run from Smyrna after the Turks invaded, something that led Seferis to feel a sense of exile which would be a major influence during his burgeoning literary career.

On his return to Athens, Seferis joined the diplomatic corps and began a successful career that saw him initially sent to England and then Albania. During the war he worked with the Free Greek Movement and only returned to the capital when Athens was liberated towards the end of the war in 1944.

He had published works during the 30s and 40s including his debut Strophe in 1931 and The Cistern all of which were influenced by the Hellenistic culture and Greek history. In 1947 he published The Thrush whilst holding a diplomatic post in Turkey. In 1953, Sefaris paid his first visit to Cyprus and feel deeply in love with the island which reminded him a great deal of his childhood with its mix of people and rolling landscape.

Cyprus inspired Serafis to write Log Book III in 1955 which reflected much of his previous preoccupations with traveling and exile. These were also politically uncertain times and he was working hard on diplomatic issues, trying to help reconcile the differences between Cyprus, Turkey and Greece.

In 1963, Sefaris became the first national to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, which recognized the role he had played in the revival of Greek writing and culture. Whilst he was often viewed as a nationalist poet, he considered himself primarily a humanist who believed in the welfare of mankind. When the right wing took control of Greece at the end of the 60s, Sefaris was one of the few to stand up and make a statement against the restrictive regime.

Sefaris read out a statement on the BBC in 1969 but was already in failing health and would not live to see the changes that saw the junta dissolved. He was instrumental in introducing modernism to Greek literature and had many notable supporters including Henry Miller and DH Lawrence who helped to translate his works.

His deep knowledge of Greek mythology and history and the way he was able to apply it to modern day life in his country, set him apart as one of the most influential poets of his day. After a period of hospitalization, Sefaris died in hospital in 1971 and his funeral drew huge crowds who were there as much to protest against the dictatorial regime as celebrate the poet’s life.