Keith Douglas, like many others of his generation, was unfortunate to be born at the time that he was. The Second World War was breaking out when he was only 19 years old so it was inevitable that he would follow his father’s former path into the Army and then, of course, take his chances with whatever dangers came his way. In truth though he was almost sanguine about the possibility of losing his life to the war and it is sad that this is exactly what happened. During his short life though he had managed to overcome a difficult childhood and grew up to be an accomplished and outward looking poet, much admired by other poets and literature scholars.

Keith Douglas, like many others of his generation, was unfortunate to be born at the time that he was. The Second World War was breaking out when he was only 19 years old so it was inevitable that he would follow his father’s former path into the Army and then, of course, take his chances with whatever dangers came his way. In truth though he was almost sanguine about the possibility of losing his life to the war and it is sad that this is exactly what happened. During his short life though he had managed to overcome a difficult childhood and grew up to be an accomplished and outward looking poet, much admired by other poets and literature scholars.

He was born in January 1920 in the Kentish town of Tunbridge Wells. His father was a retired soldier whose attempts at establishing a chicken farming business failed just at the time that Keith was being sent to preparatory school aged 6. His mother was constantly ill and the marriage broke down in 1928. Keith’s father remarried and lost touch with his son during the next ten years. During this time Keith managed to get a good education and it was while studying at Christ’s Hospital school in Horsham that his talents as a poet were first recognised. He was also known as a rebellious pupil and often in scrapes which almost led to his expulsion. As was common at that time, the school had an Officer Training Corps and Douglas was an outstanding member despite his opposition to all things military.

He knuckled down to his education though and was a model pupil, leading to his entry to Merton College, Oxford in 1938, reading English and History. His mentor sent some of Keith’s poems to T S Eliot and received an encouraging response. He was one of the featured poets in a collection called Eight Oxford Poets but this was not published until 1942 and, by this time, he was in the Army fighting in the Middle East. He was a daring, and sometimes undisciplined, officer who somehow just about managed to stay safe and out of trouble with his superiors

While serving as a tank commander in North Africa he put down his experiences in vivid fashion, including his own drawings, in a memoir called Alamein to Zem Zem. His observations at that time were seen, by some, as somewhat callous because he appeared to be taking a detached, outward looking approach to the ongoing war. He tried to keep his emotions to himself and, as a result, wrote poetry that was regarded by many to be among the finest ever written by a 20th century serving soldier.

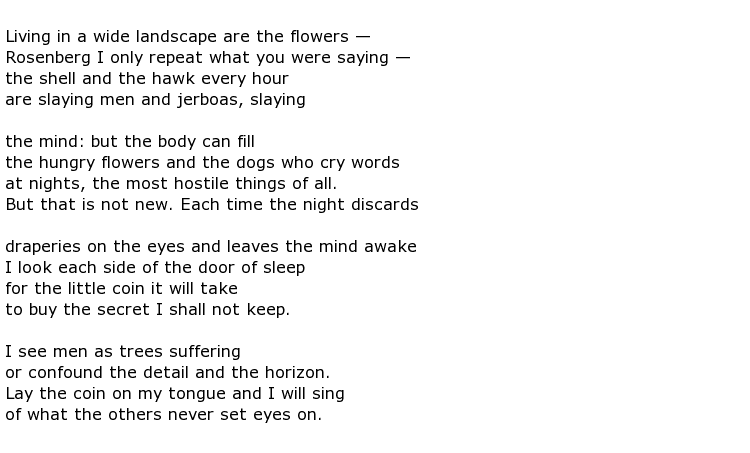

A good example is Desert Flowers which he wrote in 1943. It refers to the great First World War poet, Isaac Rosenberg. Douglas diverted the praise he got for this poem, stating that he was only repeating what had been written before. Here is the poem:

As the build up to D Day progressed Douglas found himself back in England in 1943. He trained for the invasion and went with his comrades to France on the 6th June 1944 but, within three days, he was dead.

Captain Keith Douglas was killed by enemy mortar fire on the 9th June 1944 while his regiment were trying to break out of Bayeux. He was 24 years old. His body was buried almost where he fell but eventually re-interred at Tilly-sur-Seulles War Cemetery.