It”s become fashionable to diss Edward Estlin Cummings again. Best know to the world as e. e. cummings, the way he signed his name, his fresh takes on language and wordplaying infused his poetry and made him one of the most recognized and distinctive voices in modern American poetry. You can read all about his honors and the debates about his poetry in dozens of other places. This post is a personal one – because more than any other poet, Cummings is responsible for my own voice and my love of poetry.

I think that my first Cummings poem was in-Just, with its delightful run-together words and made-up compounds (puddle-wonderful, mudlusciuos). It was irresistible to my ordered little eleven year old mind, and I thoroughly delighted in the way that the words danced on the page in unlikely combinations. That same year, probably later in the same chapter in English Lit, I discovered Anyone who lived in a pretty how town with up so floating many bells down, and I was forever hooked. In freshman year, I borrowed his 100 Poems collection from the school library, and (forgive me Sr. Mary Louise) never returned it. In the more than thirty years since then, it is the only book of the thousands that I have owned that I have never lost. It has always been with me.

It was reading Cummings that taught me to read poetry with a critical eye, to take a poem word by word and line by line and understand what the poet had put into it for me to find. Before anyone taught me the names for them, he had taught me to use tools like enjambment, onomatopeia, personification, extended metaphor, implied metaphor, slant rhyme, dissonance, assonance. He taught me how to break rules gracefully, with meaning and forethought, how to combine words into compounds that became something new and beautiful in themselves.

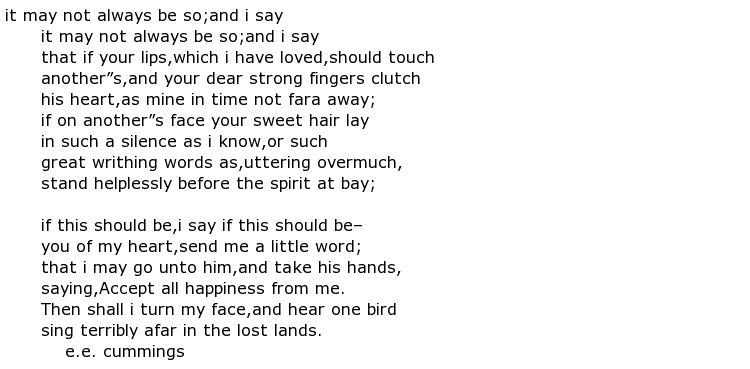

For all his vaunted unconventionality, though, the Cummings works that most drew me were his reworkings of traditional forms like the villanelle and the sonnet, and to this day, I maintain that there has never been a more beautiful love poem than his sonnet, it may not always be so, and i say. It was from those works that I learned the impact of breaking rules judiciously. Those poems were my poetic equivalent of “Civil Disobedience”, tracts that explained how and why it is important to understand the rules and the reasons that they exist before you break them, and how to break them effectively and with meaning.

So… happy birthday, Edward Estlin Cummings. And thank you.

Some Cummings poems:

If

Thy fingers make early flowers

All in green my love went riding

when god lets my body be

Buffalo Bill”s

[tags]poetry, e.e. cummings[/tags]

You must register to comment. Log in or Register.