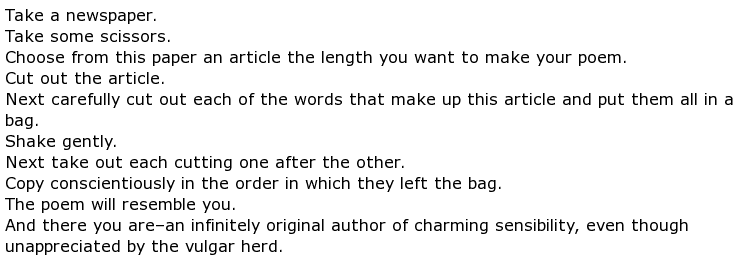

Born in Moldavia in 1896, but spending a large part of his life in France, Tristan Tzara was a poet and performance artist who had a role in many of the great movements of the early 20th Century including symbolism, cubism and the avant-garde. Raised in a Romanian Jewish family, Tzara went to school in Bucharest and by the age of 16 he was already involved in writing, helping to edit the literary magazine Simbolul.

Born in Moldavia in 1896, but spending a large part of his life in France, Tristan Tzara was a poet and performance artist who had a role in many of the great movements of the early 20th Century including symbolism, cubism and the avant-garde. Raised in a Romanian Jewish family, Tzara went to school in Bucharest and by the age of 16 he was already involved in writing, helping to edit the literary magazine Simbolul.

The magazine, though run by some young pretenders, attracted work by some of the notable poets and writers in Romania of the time, and during its short lived existence played a major role in creating the pathway for the avant-garde movement that would follow symbolism. Tzara’s first work was published in the magazine Chemarea in 1915 and he later attended university but failed to graduate.

Tzara left Romania for Switzerland and even gave up his native language to speak French exclusively. He became friends with German anarchist poet Hugo Ball and took part in shows at the Cabaret Voltaire. In this vibrant atmosphere, and partly as a retaliation against the horrific war, the Dada movement was born and Tzara was at the forefront of it.

In 1919, he moved to Paris to help edit the magazine Littérature but continued to take part in Dada activities, often running variety shows including the Théâtre de l”Œuvre where is work The First Heavenly Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine was first performed. In 1921, the Dada movement seemed to stagnate with disagreements between Tzara and another leading light, Breton.

Whilst Dadaism began to turn cold, Tzara was beginning his move towards Surrealism. He married Greta Knutson in 1925 and in 1927 was publishing work such as Of Our Birds and The Travelers’ Tree. He also became involved in film, writing scripts producing Le Cœur à Barbe on celluloid. With the rise of Hitler’s Germany, Tzara became involved in the anti-fascist movement and briefly took part in the Spanish Civil War.

At the time, he began to move from surrealism and, when World War II broke out, he moved south to Marseille to escape the German forces. He joined the French Resistance and, with the rise of antisemitism in Europe, he was stripped of his Romanian nationality. Subsequently, when the war finished, Tzara was made a French citizen and became more politically active. He continued to write, producing works such as Sign of Life in 1946 and From a Man’s Memory in 1950.

In 1956 he was in Hungary, helping to support the country’s desire for independence. He was back in Paris when the revolution broke out and thereafter started to withdraw from public life. He contented himself with researching the work of poet François Villon and writing and in 1961 he was awarded the Taormina Prize.

Throughout his life, Tzara’s poetry explored such issues as the anguished soul and the tragedy of humanity. From the days of Dadaism, he eventually transformed himself into a more mature and lyrical poet. He died in Paris in 1963 at the age of 67 and is buried at the Cimetière du Montparnasse.