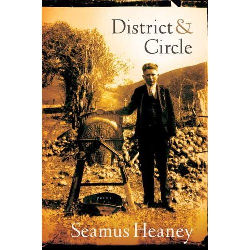

Seamus Heaney Book Cover” align=”right” />The Guardian, a UK newspaper, reported Saturday that Nobel Prize Laureate Seamus Heaney”s 12th book, District and Circle, has made the short list for the prestigious Forward Poetry Prize. Established in 1991, the Forward Poetry Prize is awarded each year to the year”s Best Collection, Best Single Poem and Best First Collection. Its £10,000 prize is one of the richest poetry prizes awarded in the UK each year.

Seamus Heaney Book Cover” align=”right” />The Guardian, a UK newspaper, reported Saturday that Nobel Prize Laureate Seamus Heaney”s 12th book, District and Circle, has made the short list for the prestigious Forward Poetry Prize. Established in 1991, the Forward Poetry Prize is awarded each year to the year”s Best Collection, Best Single Poem and Best First Collection. Its £10,000 prize is one of the richest poetry prizes awarded in the UK each year.

The Guardian article raises the question “Is it fair for Heaney, an established, well-known poet, to be entered on equal footing with competitors just publishing their second or third books?” Or, to quote them more directly,

In recent years it has been rare for artists of Heaney”s rank to be associated with poetry competitions, which are generally seen as a chance for writers with less star status.

In many ways, this minor controversy – which is, for the record, completely resolved within the Guardian”s short article – mirrors the larger one about poetry contests in general. I”m not talking here about the obvious scam contests whose only purpose is to bilk money from naive poets who end up paying for the publication of an anthology with their poem in it. I”m talking about the “legitimate” contests which have become one of the major avenues of publication for poetry in today”s world. It has become almost de rigeur for small presses to sponsor poetry contests with the prize being cash and publication of the winning book of poetry. In order to enter, the poet pays a reading fee that ranges from $10 to $40. The combined reading fees pay for the prize and the publication of the book, and help further the press itself.

The question has arisen – and was fanned into a blazing flame by Foetry.com, an alleged watchdog and whistleblower site that operated anonymously for a couple of years before the identity of its owner was revealed. Alan Cordle, a librarian and husband of a prize-winning poet, said that he started the site after many discussions with his wife about what he saw as cronyism in the awarding of prizes in many poetry contests. The fallout of his vitriolic attacks on many judges of poetry contests included a number of those judges deciding to stop judging. Those attacks also prompted many contests to create guidelines for their contests that included such things as disqualifying any poet whose work had been previously published in that press, or who had any relationship, however tenuous, with the judge(s) for that contest.

This seems on the surface a good thing, and yet it raises some troublesome questions. If an open contest is meant to choose the best book of poetry published in a particular year, is it reasonable to hamper that aim by excluding those with well-known names? In the small world of poetry, is it fair to disqualify a poet because he has taken a class with a particular judge? Is the contest paradigm simply a bad bad way to promote and publish poetry?

The answers to those questions are undoubtedly subject to viewpoint and open to interpretation. For the time being, the contest model is the one that works to bring new poets to the attention of publishers and readers. Until the market for poetry approaches that of the market for novels, nonfiction and even song lyrics, it may be the only way to go. And that, perhaps, is the most unfair part of the entire argument.

You must register to comment. Log in or Register.